How to Secure Ubuntu 16.04, 18.04, 20.04, 22.04 and 24.04

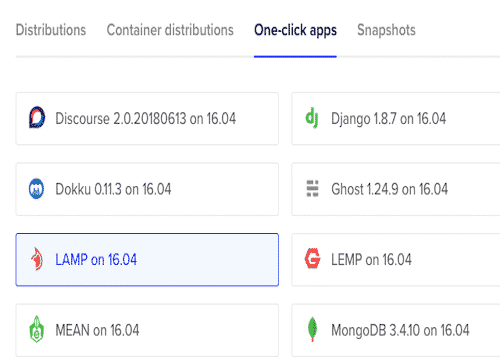

When I spin up a fresh Ubuntu server, the very first thing I do (before installing anything fancy) is lock it down. A default install of Ubuntu is not "wide open", but it's also not what I'd call production ready. A few quick changes make a huge difference to how hard it is to break into your box.

This guide will show you how I secure my own droplets and servers, from Ubuntu 16.04 right up to 24.04. I'm not a Linux security researcher and I don't pretend to understand every little thing that's going on under the hood – I just want my servers to be fast, stable and as safe as reasonably possible.

If you follow this page step by step, you'll end up with:

- Automatic security updates

- SSH locked down with keys only (no passwords, no root login)

- A firewall that only allows what you actually use

- Brute force protection for SSH and web services

- Some extra kernel and network hardening

- Cleaner logs and basic monitoring

Supported Ubuntu Versions (And a Quick Warning)

This guide works on:

- Ubuntu 16.04 (Xenial) – old, only gets security updates via ESM

- Ubuntu 18.04 (Bionic) – also ESM territory now

- Ubuntu 20.04 (Focal)

- Ubuntu 22.04 (Jammy)

- Ubuntu 24.04 (Noble)

If you're still on 16.04 or 18.04 without Extended Security Maintenance (ESM) enabled, the most important "security step" is honestly to upgrade the OS. You can still harden an older system, but no patches means you're always playing catch up.

Before You Start

You'll need:

- SSH access to your server (Putty on Windows or Terminal on Mac/Linux)

- A user that can run

sudo(or root access to start with) - Your server's IP address and, if you host websites, the domains pointing to it

In the examples below I'll assume you're logged in as a user that has sudo. If you're still logging in directly as root, we'll fix that in a minute.

Step 1 – Update Ubuntu and Clean Up

First job: make sure the system is fully up to date.

sudo apt update

sudo apt upgrade -y

sudo apt autoremove -y

I run this often. On a brand new droplet it usually pulls in a bunch of updated packages and sometimes a new kernel. If it asks you to restart services, it's normally safe to say "yes to all" on a fresh install.

Step 2 – Create a Non-Root Admin User

I never leave root SSH enabled on a public server. Instead I create a normal user and give it sudo access.

sudo adduser myadminuser

sudo usermod -aG sudo myadminuser

Pick a strong password. Once this is done, open a second terminal and test logging in as the new user:

ssh myadminuser@YOUR_SERVER_IP

Don't disable root login until you've confirmed this works.

Step 3 – Set Up SSH Keys (No Password Logins)

Passwords over SSH are just asking to be guessed or brute forced. I always switch to SSH keys as soon as possible.

- On your own computer, generate a key pair (if you don't already have one):

ssh-keygen -t ed25519

You can accept the defaults or set a passphrase if you like.

- Copy your public key to the server (from your local machine):

ssh-copy-id myadminuser@YOUR_SERVER_IP

If ssh-copy-id isn't available, you can manually copy the contents of ~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub on your computer into ~/.ssh/authorized_keys on the server.

- Test logging in with your key:

ssh myadminuser@YOUR_SERVER_IP

If it lets you in without asking for the server password (only your key passphrase, if you set one) then you're ready to lock SSH down.

Step 4 – Lock Down SSH (Disable Root & Passwords)

Now we tell SSH to stop allowing root logins and password logins.

sudo nano /etc/ssh/sshd_config

Find and set the following options (uncomment them if needed):

PermitRootLogin no

PasswordAuthentication no

PubkeyAuthentication yes

Optional extras I sometimes use:

PermitEmptyPasswords no

ChallengeResponseAuthentication no

Save and exit, then restart SSH:

sudo systemctl restart ssh

Important: keep your existing SSH session open while you test a new one. If you make a typo and lock yourself out, it's easier to fix from the working session or via your hosting control panel console.

You can also change the SSH port if you like (for example Port 2222). It doesn't "secure" SSH by itself, but it cuts down on noisy log spam from bots.

Step 5 – Enable the Firewall with UFW

Ubuntu ships with UFW (Uncomplicated Firewall). I use it on basically every box because it's easy and does the job.

Start by setting default rules:

sudo ufw default deny incoming

sudo ufw default allow outgoing

Then allow what you actually need. At a minimum you'll want SSH:

sudo ufw allow OpenSSH

Or if that doesn't exist, allow the port you're using:

sudo ufw allow 22/tcp

If you run a website:

sudo ufw allow 80/tcp

sudo ufw allow 443/tcp

Enable the firewall:

sudo ufw enable

Check the status:

sudo ufw status verbose

Once this is on, anything you haven't explicitly allowed is blocked. That alone stops a lot of random junk from hitting your services.

Step 6 – Protect SSH with Fail2ban

Fail2ban watches your logs and bans IPs that keep failing to log in. I use it mainly for SSH, but you can also use it for NGINX, Apache and other services.

sudo apt install fail2ban -y

Create a local config so updates don't overwrite it:

sudo nano /etc/fail2ban/jail.local

Basic SSH protection:

[sshd]

enabled = true

port = ssh

filter = sshd

logpath = /var/log/auth.log

maxretry = 3

findtime = 600

bantime = 86400

Save and restart:

sudo systemctl restart fail2ban

If you want to see what it's doing:

sudo fail2ban-client status sshd

On busy servers this keeps the constant SSH scanning under control.

Step 7 – Turn On Automatic Security Updates

I'd rather let the system quietly install security patches than hope I remember to log in and do it manually every week.

sudo apt install unattended-upgrades -y

sudo dpkg-reconfigure unattended-upgrades

When prompted, choose "Yes" to enable automatic security updates.

You can tweak the settings in:

/etc/apt/apt.conf.d/50unattended-upgrades

By default it will only install security updates (which is what I want on most servers).

Step 8 – Remove or Disable Services You Don’t Need

The less software you have running, the less there is to attack. On a clean Ubuntu install there usually isn't much extra junk, but it's still worth checking.

List running services:

systemctl --type=service

If you see something you definitely don't need (for example Bluetooth on a headless VPS), disable and stop it:

sudo systemctl disable bluetooth.service

sudo systemctl stop bluetooth.service

On some images, things like avahi-daemon or print services might be enabled even though the server will never print anything for anyone. I tend to turn those off.

Step 9 – AppArmor Profiles

Ubuntu uses AppArmor to confine applications so that if something is compromised, it can't easily do whatever it likes on the system.

First, make sure AppArmor is installed and running (it usually is by default):

sudo apt install apparmor apparmor-utils

sudo aa-status

You should see some profiles in enforce or complain mode. For a quick boost, you can enforce profiles for certain services:

sudo aa-enforce /etc/apparmor.d/*

I'd suggest being a bit more selective on a production box and checking that nothing breaks, but on a typical web server this is usually fine. If a profile causes problems, you can switch it back to complain mode.

Step 10 – Kernel & Network Hardening (sysctl)

This bit isn't mandatory, but it's one of those "set it once and forget it" tweaks that I include on most servers.

sudo nano /etc/sysctl.conf

Add these lines to the bottom of the file:

# Disable IP source routing

net.ipv4.conf.all.accept_source_route = 0

net.ipv4.conf.default.accept_source_route = 0

# Disable ICMP redirects

net.ipv4.conf.all.accept_redirects = 0

net.ipv4.conf.default.accept_redirects = 0

net.ipv4.conf.all.send_redirects = 0

net.ipv4.conf.default.send_redirects = 0

# Enable SYN cookies (protect against some SYN flood attacks)

net.ipv4.tcp_syncookies = 1

# Do not respond to broadcast pings

net.ipv4.icmp_echo_ignore_broadcasts = 1

# Ignore bogus ICMP errors

net.ipv4.icmp_ignore_bogus_error_responses = 1

Apply the changes:

sudo sysctl -p

If you paste something wrong you'll usually see an error straight away. In that case just fix the typo and run sysctl -p again.

Step 11 – Basic Web Server Hardening (Apache/NGINX)

Most of my Ubuntu servers end up running a web server of some sort. The exact config will depend on your setup, but there are a couple of simple tweaks I always do.

Hide Version Info in NGINX

sudo nano /etc/nginx/nginx.conf

Inside the http { } block:

server_tokens off;

Reload:

sudo systemctl reload nginx

This stops NGINX advertising its exact version in error pages and headers.

Hide Version Info in Apache

sudo a2enmod headers

sudo nano /etc/apache2/conf-available/security.conf

Set:

ServerTokens Prod

ServerSignature Off

Enable the config (if it isn't already) and reload:

sudo a2enconf security

sudo systemctl reload apache2

I also make sure all sites are served over HTTPS and use a modern TLS config. If you followed my Let's Encrypt guide, you'll already have SSL sorted. You can generate decent TLS settings from sites like the Mozilla SSL config generator and paste them into your NGINX/Apache vhosts.

Step 12 – Use Fail2ban for Web Attacks (Optional But Handy)

Fail2ban can also watch your web server logs and temporarily ban IPs hammering login pages or sending obvious junk.

In /etc/fail2ban/jail.local you can enable some of the built-in web jails. For example for NGINX:

[nginx-http-auth]

enabled = true

[nginx-botsearch]

enabled = true

Or for Apache:

[apache-auth]

enabled = true

[apache-botsearch]

enabled = true

Restart Fail2ban afterwards:

sudo systemctl restart fail2ban

This doesn't replace a proper web application firewall, but it does take the edge off some of the constant noise you see in logs.

Step 13 – Logs, Monitoring and Rootkit Checks

Logs are boring until something breaks. Then they're the only thing you care about.

On modern Ubuntu you can watch logs with:

sudo journalctl -f

For SSH auth logs specifically:

sudo tail -f /var/log/auth.log

For a quick weekly summary, you can install Logwatch:

sudo apt install logwatch -y

sudo logwatch --detail High --mailto YOUR_EMAIL --range today

If you want to go further, you can add tools like rkhunter and chkrootkit:

sudo apt install rkhunter chkrootkit -y

sudo rkhunter --update

sudo rkhunter --check

sudo chkrootkit

I don't obsess over running these daily, but they're handy to run after a weird incident or if you've inherited a server and want a sanity check.

Step 14 – Backups (The Boring But Essential Part)

None of this matters if you don't have backups. Hardware fails, people make mistakes, updates sometimes go wrong. I always make sure I have:

- Automatic off-site backups of the whole server or

- At least database dumps and website files synced somewhere not on the same disk

Most VPS providers have snapshot backups for a small extra fee. It's not exciting, but the first time you break something badly and just roll back to last night's snapshot, you'll be glad you switched it on.

Quick Recap – Your Ubuntu Security Checklist

- Update and upgrade Ubuntu (

apt update && apt upgrade). - Create a non-root sudo user and stop using root for SSH.

- Set up SSH keys and disable password logins.

- Disable

PermitRootLogininsshd_config. - Enable UFW and only allow the ports you actually need.

- Install Fail2ban to protect SSH (and optionally web services).

- Turn on automatic security updates with

unattended-upgrades. - Disable or remove services you will never use.

- Check AppArmor is running and enforce sensible profiles.

- Add basic kernel/network hardening via

/etc/sysctl.conf. - Hide version info and tighten SSL/TLS on Apache or NGINX.

- Set up basic log monitoring and at least one backup strategy.

Once you've done this once or twice it becomes muscle memory. Whenever I build a new Ubuntu box (whether it's 20.04, 22.04 or 24.04), I basically run through this same list and then move on to whatever the server is actually supposed to be doing.

If you follow the steps above, your Ubuntu server will be in a much better state than the default image your host gives you, and you'll have far fewer nasty surprises in the middle of the night.